There are places on this planet where life does not thrive, because was never welcome. These are not barren wastelands in the conventional sense, but geological refusals. Zones of negation. Pockets of the Earth where biology is not merely absent, but actively repelled. Here, the mechanisms that sustain all that is living, sunlight, moisture, breath are corrupted, inverted, or altogether missing. These are places where chemosynthesis, that obscure alternative to photosynthesis, fails not for lack of chemicals, but for lack of will. The Earth, in these wounds, does not wish to generate. It wishes only to endure in silence.

In Dallol, Ethiopia, the crust splits open into kaleidoscopic pools of acid and salt. Temperatures soar beyond the point of tolerance, and the pH sinks close to zero. The atmosphere is laced with sulfur, chlorine, and iron. The terrain, though vibrant in hue, is dead. Some scientists argue over the presence of microbial life, but even if it exists, it does so in a state of perpetual siege, an existence without comfort, without reprieve. Dallol is a furnace of color where even extremophiles blanch.

In Montana, the Berkeley Pit yawns like a failed alchemical vessel. Once a copper mine, it is now a lake of sulfuric acid and heavy metals. The water stopped reflecting the sky, it now devours it. Birds that mistake its surface for rest are poisoned mid-flight. The lake is inhospitable to fish, insects, algae, hope. It is a still, rust-colored mouth whispering death.

Farther south, the Atacama Desert sprawls across northern Chile like an exiled skin. Some regions have never known rainfall in human memory. Soil samples pulled from its driest veins return sterile devoid of visible life. It goes utterly lifeless at the microbial level. Even the air feels evacuated. NASA tests Mars rovers there. It is a preview of planetary sterility.

Then there is the Elephant’s Foot, deep within the sarcophagus of Chernobyl. A congealed mass of uranium, sand, graphite, and steel. It is not a natural feature… it is a mineral born of catastrophe, a creation of human failure. For years, its radiation was so intense that merely standing near it meant certain death. Today, the dose has waned, but no organism dares colonize its vicinity. It is a relic of unlife.

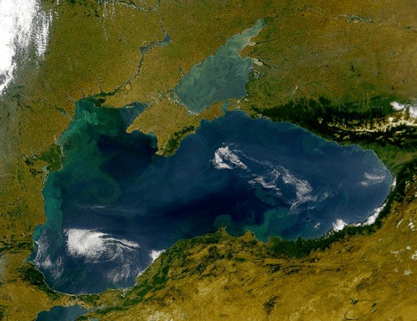

In the Black Sea, below a certain depth, oxygen vanishes. Replaced by hydrogen sulfide a toxic, corrosive vapor more suited to the mouths of volcanoes than marine environments. These anoxic zones are still, unbreathing. The bodies that descend into them do not decompose. They persist to be preserved by reverence. Even bacteria refuse the task of decay.

The McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica are a desert of ice and salt, where the wind strips moisture from rock with surgical precision. No snow settles. No roots explore. The air, dry as bleached bone, circulates without grace. Here, even the most resilient lifeforms survive only as faint traces. To stand there is to feel what the moon might feel to be untouched.

These are not mere curiosities. They are reminders. That life is not guaranteed. That the planet is not our cradle, but a shifting mass of stone and venom that occasionally tolerates us. Chemosynthesis suggests that life can emerge in the absence of light. But these places respond: even that is too generous. There are zones on this Earth where the molecules of biology drift, collide, and do nothing. No spark. No will. No genesis. Only stillness.

And then there are places that bleed:

In the frozen skin of Antarctica, from the heart of the Taylor Glacier, seeps a phenomenon called Blood Falls, a five-story wound of iron-rich brine that stains the ice like a divine hemorrhage. The water is anoxic, hypersaline, and ancient. Trapped beneath the glacier for over a million years, untouched by sun or air. When it spills, it does not bring life it summons a testimony of entrapment. Inside that red cascade: no fish, no moss, no song. Only archae, blind, ferrous, and mute. They are not life as we know it. They are a vestige, a compromise. A flicker of endurance in a landscape that fundamentally does not care.

In the end, chemosynthesis is not a miracle. It is the residue of a planet that prefers silence, but occasionally leaks blood.