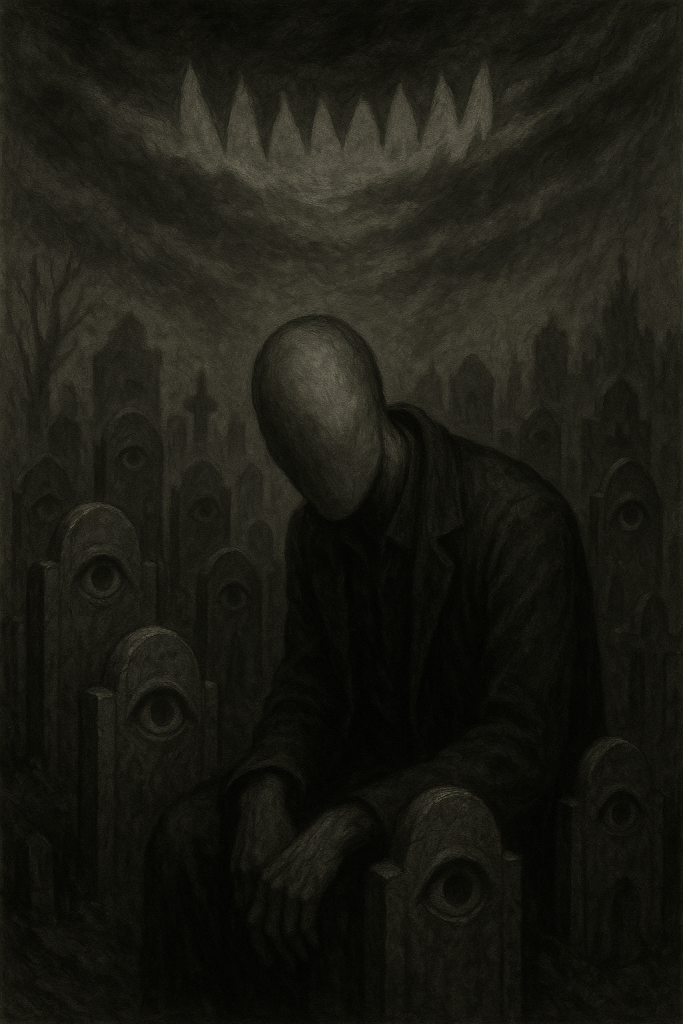

“All my griefs to this are folly; Naught so damned as melancholy.” – Robert Burton

Melancholy ancient, thick, and bitter as tar is no mere sorrow. It is the distillation of knowing too much, feeling too deeply, and surviving it nonetheless. John Donne, cloaked in shadows darker than clerical robes, penned Biathanatos not as a mere provocation but as confession, whispered beneath the crushing weight of despair. He dared ask if the soul’s last breath might, under certain stars, be sacred.

In early modern England, suicide was named felo de se literally, a felon against oneself. A legal phrase, devoid of compassion, branding the victim criminal, the corpse disgraced, impaled at crossroads, denied holy burial. A death by one’s own hand stripped estates, blackened names, and condemned souls to perpetual wandering.

Donne, irreverent theologian, suggested a scandalous mercy: perhaps not every self-homicide is sinful. He raised Christ Himself as a paradoxical figure, the divine suicide, choosing the cross knowingly. This thought was dangerous, heretical, whispered only in ink never meant for daylight.

Two decades later, Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy dissected this darkness with scholarly precision. He saw melancholy as the scholar’s disease, the philosopher’s poison, too much thinking corroding the mind. Burton chronicled black bile as more than a humor; it was cosmic ink staining every great thinker, poet, and saint.

Black bile fuels insight yet poisons the will. It gifts clarity, yet often tempts one toward ropes, blades, and quiet escapes. Burton documented the affliction thoroughly, a guidebook of despair. He did not condone suicide, but neither did he dismiss its gravity. He understood.

Historian Georges Minois, in his profound work History of Suicide: Voluntary Death in the West, adds depth to this discourse, observing that suicide, throughout history, has oscillated between condemnation and reverence, tragedy and nobility. Minois highlights how societal responses reflect deep anxieties about autonomy, suffering, and religious control. Suicide emerges as the ultimate act of personal rebellion, both feared and occasionally venerated, forcing society to confront uncomfortable truths about freedom, meaning, and human suffering.

And therein lies the dark covenant, the silent pact: the melancholic does not yearn for death out of mere sorrow, but from exhaustion of understanding, from the unbearable weight of seeing beyond illusions. Donne’s forbidden manuscript and Burton’s meticulous anatomy meet here in this shadowed understanding that the gravest sin might sometimes be the truest prayer.

This is not advocacy, nor a glorification, but acknowledgment of the depth that black bile carves into souls who think and feel too deeply. Donne, Burton, and Minois confront us with a troubling empathy: that the choice between life and death can emerge not from weakness, but from too clear a vision of existence’s harsh truths.

In a world determined to judge swiftly and harshly, these three voices whisper a hesitant mercy, allowing those haunted by black bile a fragile solace that perhaps the longing for silence, for final stillness, might not always be a betrayal, but a profoundly human plea.